- Home

- Child's Christmas 2023

- DONATE

- Mixed Doubles

- Shakespeare's Will

- A Child's Christmas in Wales

- 2020 video holiday card

- Catch a Caroler 2020

- Original

- BOOK THE COHEN SHOW!

- Lightfoot in Song

- A Midsummer Night's Dream

- King Lear

- Joni Mitchell tribute

- Cymbeline

- Grounded

- Leonard Cohen tribute

- Romeo & Juliet

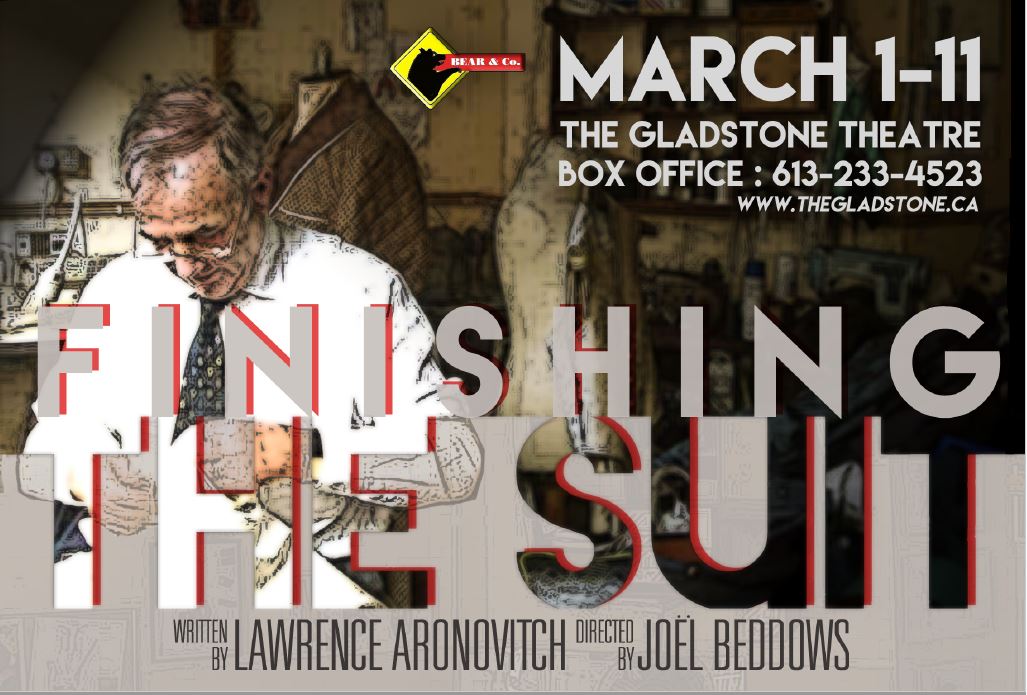

- Finishing the Suit

- Jacques Brel

- Macbeth at the Gladstone

- Macbeth: Summer Tour

- Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?

- The Tempest

- The Glass Menagerie

- Age Of Arousal

- Momma's Boy

- The Comedy Of Errors

- Windfall Jelly

- The Taming Of The Shrew

- As You Like It

- 'Tis Pity She's A Whore

- Who We Are

- Contact Us

Finishing the Suit played at The Gladstone in March 2017.

Love makes us cross oceans, throw over birthrights, overturn dynasties—or put the final touches on a bespoke suit.

Come back with Bear & Co. to 1972, when being out of the closet outside one’s home can get you jailed. But inside a Jewish tailor’s shop, all secrets are on the measuring table, as the tailor puts the finishing touches on a morning suit. Eavesdrop with us as he remembers—and mourns—the two great loves of his life: a young, brash Irish actor, and an enigmatic, battle-weary Duke.

Don't miss this tailor-made love story from the award-winning team of playwright Lawrence Aronovitch and director Joël Beddows.

Come back with Bear & Co. to 1972, when being out of the closet outside one’s home can get you jailed. But inside a Jewish tailor’s shop, all secrets are on the measuring table, as the tailor puts the finishing touches on a morning suit. Eavesdrop with us as he remembers—and mourns—the two great loves of his life: a young, brash Irish actor, and an enigmatic, battle-weary Duke.

Don't miss this tailor-made love story from the award-winning team of playwright Lawrence Aronovitch and director Joël Beddows.

SPECIAL OFFERS AND POST-SHOW EVENTS

Q&A with Playwright Lawrence Aronovitch

Join the creative force behind Finishing the Suit for an in-depth look into the process of creating this brand- new play and the mysterious tailor who inspired it.

--after the 7:30 show, March 3

--after the 2:30 show, March 4

Being Jewish and Queer: 1970s to Present

Rabbi Elizabeth Bolton offers her unique take on the relationship between faith and identity, and how attitudes have shifted in the past 40+ years.

--after the 2:30 show, March 5

Tailor-made Show & Tell: Finish the Suit!

Quilters, weavers, spinners, knitters, garment makers and fibre and fabric artists* of all kinds are invited to share their work onstage, following the performance

--after the 7:30 show, March 8

All fibre and fabric creators are welcome to take advantage of The Gladstone Theatre’s "Artist’" rate for any performance between March 2 and 11.

Join the creative force behind Finishing the Suit for an in-depth look into the process of creating this brand- new play and the mysterious tailor who inspired it.

--after the 7:30 show, March 3

--after the 2:30 show, March 4

Being Jewish and Queer: 1970s to Present

Rabbi Elizabeth Bolton offers her unique take on the relationship between faith and identity, and how attitudes have shifted in the past 40+ years.

--after the 2:30 show, March 5

Tailor-made Show & Tell: Finish the Suit!

Quilters, weavers, spinners, knitters, garment makers and fibre and fabric artists* of all kinds are invited to share their work onstage, following the performance

--after the 7:30 show, March 8

All fibre and fabric creators are welcome to take advantage of The Gladstone Theatre’s "Artist’" rate for any performance between March 2 and 11.

MEDIA

With Finishing the Suit, Bear & Co. make a valuable addition to the history of queer theatre in Ottawa. Thematically rich and dealing with important aspects of gay identity and modern British history, Suit suffers from an existential premise that perhaps draws too much attention to itself, though its strengths, as well its strong directing and design choices, outweigh any weaknesses.

Suit introduces us to a nameless tailor who has recently lost both his boyfriend Jimmy and his former employer, the Duke of Windsor. As the tailor works on the Duke’s funeral suit, he also works through his guilt and unresolved feelings for both dead men, who appear to him as physical manifestations of his thoughts. The conversation between the three focuses on the intersection of faith, gay identity, nationality, and class differences: the tailor is a working-class New York Jew, Jimmy is (was?) a dancer from a poor family in Ireland, and the Duke (or David, as he was personally known) was formerly the King of England. There’s a lot of material to work with as a result: the emotional heart of the play focuses on the tailor’s relationships with the Duke, and later Jimmy, and while the other themes inform and help to colour the love story, they can at times distract from it.

Jimmy, as a poor Irishman, mocks and teases the Duke, which not only reflects his own personal jealousy of the former object of the tailor’s affections, but also touches on the problematic relationship between Ireland and England that reached a violent climax in the late 20th century. It’s a lovely allusion, though it does rather depend on one’s knowledge of modern British history in order to appreciate the connections between the story itself and the broader cultural implications for those involved in it. The non-linear nature of the narrative does mitigate this dependence on external knowledge, though it does take away from the story itself.

Let me explain: Finishing the Suit has a rather existential premise, in that the three characters are in a small space that none of them seem able to leave, à la Sartre’s No Exit. Unlike No Exit, however, these characters all have connections to each other (albeit an indirect connection between the Duke and Jimmy) from before their time in the confined space. Due to this choice of convention, the story has already happened before the start of the play, and the characters talk about the story rather than enact it – mostly.

Though we are occasionally treated to re-enactments of moments between the characters in life – the first meeting between the tailor and the Duke, for example – the bulk of Suit is the imaginary meeting in the tailor’s mind. The tailor already knows what happened, so it’s up to the audience to piece the story together through fragmentary references in the conversation. For the most part, this sophisticated dramaturgy is consistent: the fragmented, non-linear narrative works very well with the basic memory-play premise. As an audience member, however, this narrative style can be frustrating at times, as the normal pattern of cause-and-effect that one typically expects in a drama is subverted – you’ve been warned.

Joël Beddows’ direction keeps the tensions and pauses in the conversation smoothly flowing from one topic to the next, as the tailor attempts to smooth over the turbulence between his projections of the Duke and Jimmy, with mixed results.

The stretches where two characters converse with one another to the exclusion of the third are nicely managed, with each character relegated to his own segment of the stage, overhearing the others but helpless to stop them.

The overall designs are minimalistic, pared down to the bare essentials, yet they correspond with the premise and themes wonderfully. Ivo Valentik’s set, consisting of ribbons of dark fabric, hangs down from the lighting-grid, car-wash curtain-style, filling the space with “walls” that part at the slightest touch. These ‘walls’ are organized in a surprisingly elaborate manner, creating cathedral-like vaults that may remind one of a church or synagogue, or even the medieval-inspired set design for the original production of the Broadway musical Camelot (all three are relevant, though the third has a direct connection to the storyline).

Al Connors’ sound design is similarly minimalist, the notable aspect being the West Side Story-ish whistling that the tailor hears, announcing the arrival and departure of Jimmy and the Duke in his mind. Angela Haché’s costume designs similarly evokes West Side Story in Jimmy’s appearance (not at all irrelevant for a singing, dancing boy from a poor family who’s had to rely on street smarts). The tailor and the Duke are more stereotypically dressed, but the most important aspect (to my mind, at least) is that everyone’s costume fits just about perfectly: remember, we’re not seeing the characters as they really were, we’re seeing them as the tailor imagines them.

The actors’ performances are generally strong, with the highlight being the energy between Matt Pilipiak and Isaac Giles as the tailor and Jimmy, respectively. The two exchange several stage kisses that always seem to organically arise from the tensions in their conversation, and their facial expressions when they look at each other never feel forced. David Whiteley brings a sort of lazy imperiousness to the Duke, which seems entirely in keeping with the kindly yet privileged persona that Aronovitch assigns to his interpretation of the historical figure (and somewhat kinder than the portrayals of the Duke of Windsor in other media, notably The King’s Speech and The Crown).

The avant-garde nature of the dramaturgy demands a more active listening experience on the part of the spectator, but if my only real criticism is that the production challenges the audience to pay attention, then we’re in a good place. It’s also heartening to see new work that touches on emotionally raw aspects of gay life rather than the omnipresent (and cliché) issue of social acceptance. These aspects include loving and respecting the parent who doesn’t understand you, the impossible dream of having a child (though this is increasingly becoming a non-issue today, it was very much the reality of the time), frustration with religion, unrequited love for straight men, and the exhilaration of finally meeting someone who loves you back. That these aspects of gay life are explored in a piece that engages in topics beyond the stereotypical “queer theatre” themes is heartening, and a sign that even Ottawa, with its limited amount of LGBT programming, is a place for meaningful, intelligent, and insightful theatre queer- theatre that you don’t have to be gay to get.

Suit introduces us to a nameless tailor who has recently lost both his boyfriend Jimmy and his former employer, the Duke of Windsor. As the tailor works on the Duke’s funeral suit, he also works through his guilt and unresolved feelings for both dead men, who appear to him as physical manifestations of his thoughts. The conversation between the three focuses on the intersection of faith, gay identity, nationality, and class differences: the tailor is a working-class New York Jew, Jimmy is (was?) a dancer from a poor family in Ireland, and the Duke (or David, as he was personally known) was formerly the King of England. There’s a lot of material to work with as a result: the emotional heart of the play focuses on the tailor’s relationships with the Duke, and later Jimmy, and while the other themes inform and help to colour the love story, they can at times distract from it.

Jimmy, as a poor Irishman, mocks and teases the Duke, which not only reflects his own personal jealousy of the former object of the tailor’s affections, but also touches on the problematic relationship between Ireland and England that reached a violent climax in the late 20th century. It’s a lovely allusion, though it does rather depend on one’s knowledge of modern British history in order to appreciate the connections between the story itself and the broader cultural implications for those involved in it. The non-linear nature of the narrative does mitigate this dependence on external knowledge, though it does take away from the story itself.

Let me explain: Finishing the Suit has a rather existential premise, in that the three characters are in a small space that none of them seem able to leave, à la Sartre’s No Exit. Unlike No Exit, however, these characters all have connections to each other (albeit an indirect connection between the Duke and Jimmy) from before their time in the confined space. Due to this choice of convention, the story has already happened before the start of the play, and the characters talk about the story rather than enact it – mostly.

Though we are occasionally treated to re-enactments of moments between the characters in life – the first meeting between the tailor and the Duke, for example – the bulk of Suit is the imaginary meeting in the tailor’s mind. The tailor already knows what happened, so it’s up to the audience to piece the story together through fragmentary references in the conversation. For the most part, this sophisticated dramaturgy is consistent: the fragmented, non-linear narrative works very well with the basic memory-play premise. As an audience member, however, this narrative style can be frustrating at times, as the normal pattern of cause-and-effect that one typically expects in a drama is subverted – you’ve been warned.

Joël Beddows’ direction keeps the tensions and pauses in the conversation smoothly flowing from one topic to the next, as the tailor attempts to smooth over the turbulence between his projections of the Duke and Jimmy, with mixed results.

The stretches where two characters converse with one another to the exclusion of the third are nicely managed, with each character relegated to his own segment of the stage, overhearing the others but helpless to stop them.

The overall designs are minimalistic, pared down to the bare essentials, yet they correspond with the premise and themes wonderfully. Ivo Valentik’s set, consisting of ribbons of dark fabric, hangs down from the lighting-grid, car-wash curtain-style, filling the space with “walls” that part at the slightest touch. These ‘walls’ are organized in a surprisingly elaborate manner, creating cathedral-like vaults that may remind one of a church or synagogue, or even the medieval-inspired set design for the original production of the Broadway musical Camelot (all three are relevant, though the third has a direct connection to the storyline).

Al Connors’ sound design is similarly minimalist, the notable aspect being the West Side Story-ish whistling that the tailor hears, announcing the arrival and departure of Jimmy and the Duke in his mind. Angela Haché’s costume designs similarly evokes West Side Story in Jimmy’s appearance (not at all irrelevant for a singing, dancing boy from a poor family who’s had to rely on street smarts). The tailor and the Duke are more stereotypically dressed, but the most important aspect (to my mind, at least) is that everyone’s costume fits just about perfectly: remember, we’re not seeing the characters as they really were, we’re seeing them as the tailor imagines them.

The actors’ performances are generally strong, with the highlight being the energy between Matt Pilipiak and Isaac Giles as the tailor and Jimmy, respectively. The two exchange several stage kisses that always seem to organically arise from the tensions in their conversation, and their facial expressions when they look at each other never feel forced. David Whiteley brings a sort of lazy imperiousness to the Duke, which seems entirely in keeping with the kindly yet privileged persona that Aronovitch assigns to his interpretation of the historical figure (and somewhat kinder than the portrayals of the Duke of Windsor in other media, notably The King’s Speech and The Crown).

The avant-garde nature of the dramaturgy demands a more active listening experience on the part of the spectator, but if my only real criticism is that the production challenges the audience to pay attention, then we’re in a good place. It’s also heartening to see new work that touches on emotionally raw aspects of gay life rather than the omnipresent (and cliché) issue of social acceptance. These aspects include loving and respecting the parent who doesn’t understand you, the impossible dream of having a child (though this is increasingly becoming a non-issue today, it was very much the reality of the time), frustration with religion, unrequited love for straight men, and the exhilaration of finally meeting someone who loves you back. That these aspects of gay life are explored in a piece that engages in topics beyond the stereotypical “queer theatre” themes is heartening, and a sign that even Ottawa, with its limited amount of LGBT programming, is a place for meaningful, intelligent, and insightful theatre queer- theatre that you don’t have to be gay to get.

Review by Allyson Domanski for Ottawa Tonite

I loved this play’s premise.

Skilled playwright Lawrence Aronovitch stitches a piece so fine that its touch to your skin is that of raw silk: coarse yet pleasing. Its plausibility came on to me as would a lover, its story revealing itself as would an emotional undressing to nakedness. All that, with no more than the unbuttoning of a shirt.

Bear & Co.’s production of Finishing the Suit, at The Gladstone for a much-too-limited run until March 11th, is indeed a love story but a most unconventional one. Full of regret at what was not—“sometimes love is incompatible with one’s duties,” says the Tailor—it is nonetheless full of hope for what might yet be. In the middle is the struggle to come to terms with what is: the realisation that one man was in love with two others at once, though not within a love triangle.

The play opens with the unmistakable zzzzzzzzz of a sewing machine operating. Seconds later SNAP, something breaks. A bearded man with a measuring tape draped round his neck appears, annoyed that he must resort to a hand-stitch to meet the deadline of an eminent commission: finishing the mourning suit (in this instance with a ‘u’) for a client receiving a state funeral.

The Tailor (sewn up exquisitely by Matt Pilipiak) is a New York Jew whose talent, taught by his conservative synagogue-going father, made him not only costume-maker to Broadway shows but suit-maker to a king. Rather, an ex-king.

His client is none other than the Duke of Windsor (fashioned elegantly by David Whiteley), the erstwhile King Edward VIII who abdicated to marry the unacceptable American divorcee Mrs. Wallis Simpson.(Upheld as one of the great love stories of the 20th century, it has since emerged that not only did Duchess Wallis cheat on the man who forfeited the British Crown for her but that he too, the Duke, had carried on a long-time love affair, a gay one, with his equerry nicknamed ‘Fruity.’)

It is therefore plausible that the Duke, for whom fine attire was de rigeur, would have engaged the services of an exceptional tailor recommended by his wife on a trip to New York. Equally plausible is that the Duke and his tailor could have been lovers, as this play so cheekily purports.

Their affair, it seems, was not lost on the Duchess. Despite having no role in the production other than ethereal nemesis, we learn how she made her jealousy and displeasure known by subjecting the Tailor to the cruellest of insults aimed at his faith, which takes aback even the Duke.

Pushing all these buttons to get at what’s been going on all along is the Tailor’s Irish boyfriend Jimmy (an impeccable fit by Isaac Giles). Jimmy’s ’Derry lilt and youthful cockiness is the antithesis of the Duke’s English refinement. There’s more jealousy afoot—“You didn’t make so much as a ribbon for me, Love,” digs Jimmy to the Tailor.

Most of Jimmy’s antipathy toward the Duke is political: British soldiers opened fire on Derry protestors and killed a dozen of them in the Bloody Sunday massacre.

Among those shot dead was Jimmy.

Joël Beddows coaxed seamlessly delivered accents from the principals, who likewise wove in notions of status and class into their roles. Look out for the kid from Sioux Lookout; Isaac Giles as Jimmy has all the makings of a William Hurt in Kiss of the Spider Woman.The ribbons galore that set designer Ivo Valentik hung from the rafters (1200 yards in total, like so many unfolded neckties) and a few additional minimalist touches (a male tailor form shouldering the unfinished mourning suit, plus a tape measure) structured things just right.

Costume designer Angela Haché attired her men as befit their standing: a beige linen-looking suit comprising jacket, waistcoat and trousers, with a shirt and tie for the Duke; a white shirt, tie, dark vest and pants for the Tailor; leather jacket, t-shirt, jeans and sneakers for Jimmy.

Finishing the Suit is a fine piece of theatre whose quality acting tells a beguiling story that had me walking out believing something like this could have happened. I love when a play can do that.

Skilled playwright Lawrence Aronovitch stitches a piece so fine that its touch to your skin is that of raw silk: coarse yet pleasing. Its plausibility came on to me as would a lover, its story revealing itself as would an emotional undressing to nakedness. All that, with no more than the unbuttoning of a shirt.

Bear & Co.’s production of Finishing the Suit, at The Gladstone for a much-too-limited run until March 11th, is indeed a love story but a most unconventional one. Full of regret at what was not—“sometimes love is incompatible with one’s duties,” says the Tailor—it is nonetheless full of hope for what might yet be. In the middle is the struggle to come to terms with what is: the realisation that one man was in love with two others at once, though not within a love triangle.

The play opens with the unmistakable zzzzzzzzz of a sewing machine operating. Seconds later SNAP, something breaks. A bearded man with a measuring tape draped round his neck appears, annoyed that he must resort to a hand-stitch to meet the deadline of an eminent commission: finishing the mourning suit (in this instance with a ‘u’) for a client receiving a state funeral.

The Tailor (sewn up exquisitely by Matt Pilipiak) is a New York Jew whose talent, taught by his conservative synagogue-going father, made him not only costume-maker to Broadway shows but suit-maker to a king. Rather, an ex-king.

His client is none other than the Duke of Windsor (fashioned elegantly by David Whiteley), the erstwhile King Edward VIII who abdicated to marry the unacceptable American divorcee Mrs. Wallis Simpson.(Upheld as one of the great love stories of the 20th century, it has since emerged that not only did Duchess Wallis cheat on the man who forfeited the British Crown for her but that he too, the Duke, had carried on a long-time love affair, a gay one, with his equerry nicknamed ‘Fruity.’)

It is therefore plausible that the Duke, for whom fine attire was de rigeur, would have engaged the services of an exceptional tailor recommended by his wife on a trip to New York. Equally plausible is that the Duke and his tailor could have been lovers, as this play so cheekily purports.

Their affair, it seems, was not lost on the Duchess. Despite having no role in the production other than ethereal nemesis, we learn how she made her jealousy and displeasure known by subjecting the Tailor to the cruellest of insults aimed at his faith, which takes aback even the Duke.

Pushing all these buttons to get at what’s been going on all along is the Tailor’s Irish boyfriend Jimmy (an impeccable fit by Isaac Giles). Jimmy’s ’Derry lilt and youthful cockiness is the antithesis of the Duke’s English refinement. There’s more jealousy afoot—“You didn’t make so much as a ribbon for me, Love,” digs Jimmy to the Tailor.

Most of Jimmy’s antipathy toward the Duke is political: British soldiers opened fire on Derry protestors and killed a dozen of them in the Bloody Sunday massacre.

Among those shot dead was Jimmy.

Joël Beddows coaxed seamlessly delivered accents from the principals, who likewise wove in notions of status and class into their roles. Look out for the kid from Sioux Lookout; Isaac Giles as Jimmy has all the makings of a William Hurt in Kiss of the Spider Woman.The ribbons galore that set designer Ivo Valentik hung from the rafters (1200 yards in total, like so many unfolded neckties) and a few additional minimalist touches (a male tailor form shouldering the unfinished mourning suit, plus a tape measure) structured things just right.

Costume designer Angela Haché attired her men as befit their standing: a beige linen-looking suit comprising jacket, waistcoat and trousers, with a shirt and tie for the Duke; a white shirt, tie, dark vest and pants for the Tailor; leather jacket, t-shirt, jeans and sneakers for Jimmy.

Finishing the Suit is a fine piece of theatre whose quality acting tells a beguiling story that had me walking out believing something like this could have happened. I love when a play can do that.

Review by Barbara Popel for Apt 613

My first reaction to Bear and Company’s production of Ottawa playwright Lawrence Aronovitch’s Finishing the Suit was, “I have to check some dates in Wikipedia.”

Wikipedia told me that the play takes place in 1972, shortly after the Duke of Windsor died. For those of you who aren’t up on your British royal history, King Edward VIII abdicated the throne in December 1936 in order to marry twice-divorced American Wallis Simpson. He became the Duke of Windsor in March 1937.

The play is a memory piece about grief. A fictional New York City Jewish tailor is visited by two ghosts. One is the Duke of Windsor (known to his friends as David), whose funeral coat he is making. The tailor was in his early 20s when he first met the Duke. He moved to Paris to be the Duke’s personal tailor.

The other ghost is the tailor’s great love, Jimmy. Jimmy was a young actor from Northern Ireland who performed in several Broadway musicals and who was killed on Bloody Sunday in Derry on January 30, 1972.

There’s another ghost haunting the tailor’s memories – his Yiddish father. By the time of the play, the tailor has become a successful Broadway costume designer. We learn that the tailor returned from Paris to his first Broadway job on Camelot. Camelot opened in December 1960. That’s where the tailor met Jimmy, who was a dancer in the Camelot chorus.

This may all seem a rather fanciful setup, but (thank you, Wikipedia), it’s based on a couple of historical characters. One of them is the Duke of Windsor/David. The other is a very successful Los Angeles stage and film designer named Tony Duquette who, after World War II, lived in Paris for a year and actually did do some commissions for the Duke and Duchess of Windsor. Years later, Duquette replaced Camelot’s costume designer, Adrian, who had died in September 1959.

So, piecing the play’s timeline together, I think the tailor probably met the Duke in the early 1950s, lived with the Duke and Duchess in Paris until 1959, and met Jimmy in late 1959 or early 1960 in New York. Jimmy and the Duke both died in 1972. The Duke was 77. In 1972, the fictional tailor was probably in his 40s and Jimmy was in his 30s.

Why am I fixating on dates? Because the actors cast as the Duke and the tailor are far too young. As the Duke, David Whiteley is a robust middle-aged man, not a frail septuagenarian. As the tailor, Matt Pilipiak looks to be on the sunny side of 30. Even Isaac Giles seems a bit young for the part of Jimmy. I’m not sure why Joël Beddows, the director, has cast the play this way, but for me it was quite jarring.

Whiteley’s accent is rock-solid. The same can’t be said for Giles, whose Bogside accent wanders all over the map. At times it may imitate a lower class Northern Irish accent (I’m no expert) but at other times it sounds distinctly middle class mid-Atlantic. Perhaps it was opening night jitters. Pilipiak doesn’t assay a New Yawk accent (he sounds Canadian to my ears), and unfortunately when he imitates his Lower East Side Yiddish father, he sounds like Don Corleone.Whiteley does an admirable job of playing an upper class twit, reminding us that historians still debate if the Duke of Windsor was as stupid as he appeared or if it was a ruse so he could do as he pleased. I’ve never bought into the “dumb as a post” theory about the Duke of Windsor, so my credulity was strained when Aronovitch has the Duke not understand the tailor’s initial question, “How do you dress?” C’mon, every one of the Duke’s tailors would have asked the same question! And that the Duke is clueless about what the gift of a salt pork cake would mean to a Jew… that was really over the top. There was evidence that the Duke was a Nazi sympathizer and racist, so it’s not believable that he was ignorant of Jewish dietary precepts.

Some folks in the opening night audience laughed at some of the lines. I’m not certain this was always Aronovitch’s intent, given the subject matter – how to cope with grief after losing loved ones.

Wikipedia told me that the play takes place in 1972, shortly after the Duke of Windsor died. For those of you who aren’t up on your British royal history, King Edward VIII abdicated the throne in December 1936 in order to marry twice-divorced American Wallis Simpson. He became the Duke of Windsor in March 1937.

The play is a memory piece about grief. A fictional New York City Jewish tailor is visited by two ghosts. One is the Duke of Windsor (known to his friends as David), whose funeral coat he is making. The tailor was in his early 20s when he first met the Duke. He moved to Paris to be the Duke’s personal tailor.

The other ghost is the tailor’s great love, Jimmy. Jimmy was a young actor from Northern Ireland who performed in several Broadway musicals and who was killed on Bloody Sunday in Derry on January 30, 1972.

There’s another ghost haunting the tailor’s memories – his Yiddish father. By the time of the play, the tailor has become a successful Broadway costume designer. We learn that the tailor returned from Paris to his first Broadway job on Camelot. Camelot opened in December 1960. That’s where the tailor met Jimmy, who was a dancer in the Camelot chorus.

This may all seem a rather fanciful setup, but (thank you, Wikipedia), it’s based on a couple of historical characters. One of them is the Duke of Windsor/David. The other is a very successful Los Angeles stage and film designer named Tony Duquette who, after World War II, lived in Paris for a year and actually did do some commissions for the Duke and Duchess of Windsor. Years later, Duquette replaced Camelot’s costume designer, Adrian, who had died in September 1959.

So, piecing the play’s timeline together, I think the tailor probably met the Duke in the early 1950s, lived with the Duke and Duchess in Paris until 1959, and met Jimmy in late 1959 or early 1960 in New York. Jimmy and the Duke both died in 1972. The Duke was 77. In 1972, the fictional tailor was probably in his 40s and Jimmy was in his 30s.

Why am I fixating on dates? Because the actors cast as the Duke and the tailor are far too young. As the Duke, David Whiteley is a robust middle-aged man, not a frail septuagenarian. As the tailor, Matt Pilipiak looks to be on the sunny side of 30. Even Isaac Giles seems a bit young for the part of Jimmy. I’m not sure why Joël Beddows, the director, has cast the play this way, but for me it was quite jarring.

Whiteley’s accent is rock-solid. The same can’t be said for Giles, whose Bogside accent wanders all over the map. At times it may imitate a lower class Northern Irish accent (I’m no expert) but at other times it sounds distinctly middle class mid-Atlantic. Perhaps it was opening night jitters. Pilipiak doesn’t assay a New Yawk accent (he sounds Canadian to my ears), and unfortunately when he imitates his Lower East Side Yiddish father, he sounds like Don Corleone.Whiteley does an admirable job of playing an upper class twit, reminding us that historians still debate if the Duke of Windsor was as stupid as he appeared or if it was a ruse so he could do as he pleased. I’ve never bought into the “dumb as a post” theory about the Duke of Windsor, so my credulity was strained when Aronovitch has the Duke not understand the tailor’s initial question, “How do you dress?” C’mon, every one of the Duke’s tailors would have asked the same question! And that the Duke is clueless about what the gift of a salt pork cake would mean to a Jew… that was really over the top. There was evidence that the Duke was a Nazi sympathizer and racist, so it’s not believable that he was ignorant of Jewish dietary precepts.

Some folks in the opening night audience laughed at some of the lines. I’m not certain this was always Aronovitch’s intent, given the subject matter – how to cope with grief after losing loved ones.

THE CREATIVE AND PRODUCTION TEAM

Playwright: Lawrence Aronovitch

Lawrence is a Canadian playwright from Montreal. His journey to this occupation was a roundabout one. After studying history and physics at Harvard and working in the American and Canadian space programs, Lawrence began to write plays in 2007. Curiously, the many experiences he's had outside the theatre have helped inform his writing on issues important to him. A former playwright in residence at the Great Canadian Theatre Company, he has written plays about scientists (Marie Curie), poets (W.H. Auden), politicians (Ezekiel Hart), and movie stars (Hedy Lamarr). This is his first play about tailors, dancers, and ex-kings.

Director: Joël Beddows

Over the past two decades, Joël has pursued creative projects that lie at the crux of social critique, poetry, and symbolism. Whether he is directing a new play, a text drawn from the canon, or a production for young audiences, Beddows considers every project an opportunity for questioning our contemporary world and its rapport with imagination, history, and collective memory. Beddows’ directing credits include Rage by Michele Riml, The Empire Builders by Boris Vian, Happy Days by Samuel Beckett, Frères d’hiver by Michel Ouellette, East of Berlin by Hannah Moscovitch, À tu et à moi by Sarah Migneron, Visage de feu by Marius von Mayenburg , Petites bûches by Jean-Philippe Lehoux, and Un neurinome sur une balançoire by Alain Doom.

The Tailor: Matt Pilipiak

Born and raised in the Prairies, Matt is a Toronto-based actor, producer, writer, and dramaturge. Matt is thrilled to be back in Ottawa after performing in Just Mingling: A Queer Salon last year and Pea Green Theatre’s Three Men in a Boat the previous year in the Ottawa Fringe. Other credits include: Peter Pan (Bad Hats Theatre), A Midsummer Night’s Dream (Humber River Shakespeare), The Wedding Singer (Hart House Theatre), War of the Roses: A Game of Kings (Theatre Aquarius), Macbeth and Comedy of Errors (Shakespeare on the Sask). Matt is also the managing director of the Toronto-based indie theatre company Bad Hats Theatre. He is a proud graduate of George Brown’s Classical Acting Conservatory.

Jimmy: Isaac Giles

Isaac is a Toronto-based actor originally from Sioux Lookout in northwestern Ontario. He is excited to join the team in his second show with Bear & Co., and his first on the Gladstone stage. Isaac is a graduate of the joint Theatre and Drama Studies program at Sheridan College and Univeristy of Toronto Mississauga. Recent credits include Ferdinand/Caliban in The Tempest (Bear & Co.); Demetrius/Flute in A Midsummer Night’s Dream (Humber River Shakespeare Company); Constantine Treplyov in The Seagull, Menolaos in Orestes (Theatre Erindale). This summer, Isaac will be performing at the Stratford Festival as the Juggler in The Madwoman of Chaillot. He is grateful to be a part of this beautiful play with this talented group.

The Duke: David Ross Whiteley

David is delighted to be working with Bear & Co. again after previously appearing in their Wild West take on Comedy of Errors. Often seen at The Gladstone both onstage and off, David has appeared most recently in Tuesdays with Morrie (SevenThirty Productions), The Norman Conquests (Plosive/SevenThirty Productions,) and Venus in Fur (Plosive Productions), and directed this fall’s Romeo & Juliet REDUX and last spring’s Vanya and Sonia and Masha and Spike. Beyond The Gladstone, David has recently been seen at the NAC in Anne & Gilbert: The Musical, in Vancouver in Mozart & Salieri (Seven Tyrants), and in a Sandy Hill found-venue staging of Frankie and Johnny in the Clair de Lune (Vacant House). David will be returning to The Gladstone in May to perform in both English and French versions of Mæstro.

Stage Manager: Lauriane Lehouillier

As an artist, Lauriane works mostly in French. She has a bachelor's degree in theater from the University of Ottawa and a master’s degree with a specialization in objects theatre. Lately, she has created Les ailes cassées with Théâtre Tremplin. As an actress, she was in Premières de classe (Théâtre de la Barouette), Les Z’aventures of Zozote (Théâtre de Dehors), Ce qui meurt en dernier (Obviously, a Theatre Company) and L’Hyper Talk Show (Theater Dérives Urbaines). As a stage manager, Lauriane has worked on shows such as Charlotte (Vox Théâtre), La Petite Poule d’eau (Théâtre de l’île) and The Pretentious Young Ladies (Obviously, a Theater Company). As a creator, she presented L’Iliade pour les nuls in Iqaluit and participated in the Théâtre de l’île’s staging laboratory, Regard sur Cocteau.

Set Design: Ivo Valentik

Ivo has worked as a goat herder, architect, professor, contractor, historic restorer, and now again for the first time in four years since his lovely, time-consuming son was born, a set designer. In his prior years in set design he was nominated four times for a Capital Critics Circle Award (winning 2009, 2011, and 2012) and nine times for the Prix Rideau Awards, capturing Emerging

Artist in 2008 and five Outstanding Set Design awards (2008 Iron , 7:30 Productions; 2009 Midwinter’s Dream Tale, A Company of Fools; 2010 Afghanistan, Théâtre la Catapulte; 2011 Speed the Plow, Plosive Productions; and 2012 East of Berlin, GCTC).

Artist in 2008 and five Outstanding Set Design awards (2008 Iron , 7:30 Productions; 2009 Midwinter’s Dream Tale, A Company of Fools; 2010 Afghanistan, Théâtre la Catapulte; 2011 Speed the Plow, Plosive Productions; and 2012 East of Berlin, GCTC).

Costume Design: Angela Haché

A graduate in visual arts and education from l’ Université de Moncton, Angela Haché soon start working in theatre as a costume designer. As such, she has worked in television and cinema but mostly in theatre, which she prefers. Thanks to touring productions, her designs have been seen both locally and nationally. Her most recent work includes La Locandiera, Les Reines, Cinéma, and Marat/Sade. She is presently employed by the University Of Ottawa, Department of Theatre, where she is resident designer in charge of wardrobe. Finishing the Suit is her sixth costume design for director Joël Beddows. Their collaborations include The Empire Builders (Third Wall Theatre) for which she received a Prix Rideau Awards for Outstanding Costume Design.

Angela is thrilled to be associated with this collaborative project, a first in her career.

Angela is thrilled to be associated with this collaborative project, a first in her career.

Lighting Design: David Magladry

David Magladry has been a professional lighting and set designer for over 20 years, working in theatre, television, museum exhibitions, and special events. Clients include Bear & Co., Plosive Productions, the Great Canadian Theatre Company, Eddy May Productions, Algonquin College Theatre Department, Classic Theatre, The Canadian Museum of History and The Canadian War Museum.

Recent projects include working with Christopher Plummer on his “Shakespeare and Music” concert here in Ottawa, on Bear and Co.'s MacBeth, and for the St. Lawrence College productions of The Wizard of Oz and Twelfth Night.

Recent projects include working with Christopher Plummer on his “Shakespeare and Music” concert here in Ottawa, on Bear and Co.'s MacBeth, and for the St. Lawrence College productions of The Wizard of Oz and Twelfth Night.

Sound Design: AL Connors

An energetic, passionate, creative partner in everything he does, AL Connors is one of Canada’s most respected names in improvisation. He’s an educator, producer, director, performer, and designer who enjoys working in all aspects of live, interactive performance and education. He is currently teaching improvisation, in the context of leadership skills, as a part of the Telfer School of Management at University of Ottawa’s new Executive MBA in Complex Project Leadership. He also regularly teaches workshops on behalf of the National Arts Centre and the Great Canadian Theatre Company. An award-winning sound designer, AL has recently designed Pierre Brault's Will Somers at the GCTC; Much Ado About Feckin' Pirates at the Undercurrents, Toronto Festival of Clowns, and Springworks Festivals; The 39 Steps and Noises Off for SevenThirty Productions; and the awards-winning Wolf Child and HROSES for MiCasa Theatre.

Assistant Stage Manager: May Abu-Shaban

May Abu-Shaban is an Ottawa-based, multilingual (English, French, Arabic, and Spanish) theatre artist who is in the fourth year of her Honours Bachelor of Arts with a Specialization in Theatre at the University of Ottawa. Past credits include Sleep My Baby Sleep (production manager, Unicorn Theatre), Serial Killer (production manager, Théâtre de la licorne), La Locandiera (sound designer, La Comédie des Deux Rives), and A Midsummer Night's Dream (stage manager, Taboo! Productions). May hopes to spend the next few years experimenting with unconventional stage and audience configurations that incorporate the use of technology to tell stories in unexpected ways. She is thrilled to be working with the wonderful production and design teams and the very talented cast of Finishing the Suit!